| site search by freefind | advanced |

- Home

- History Stories

- Stories of Adventure

- Forest Fire

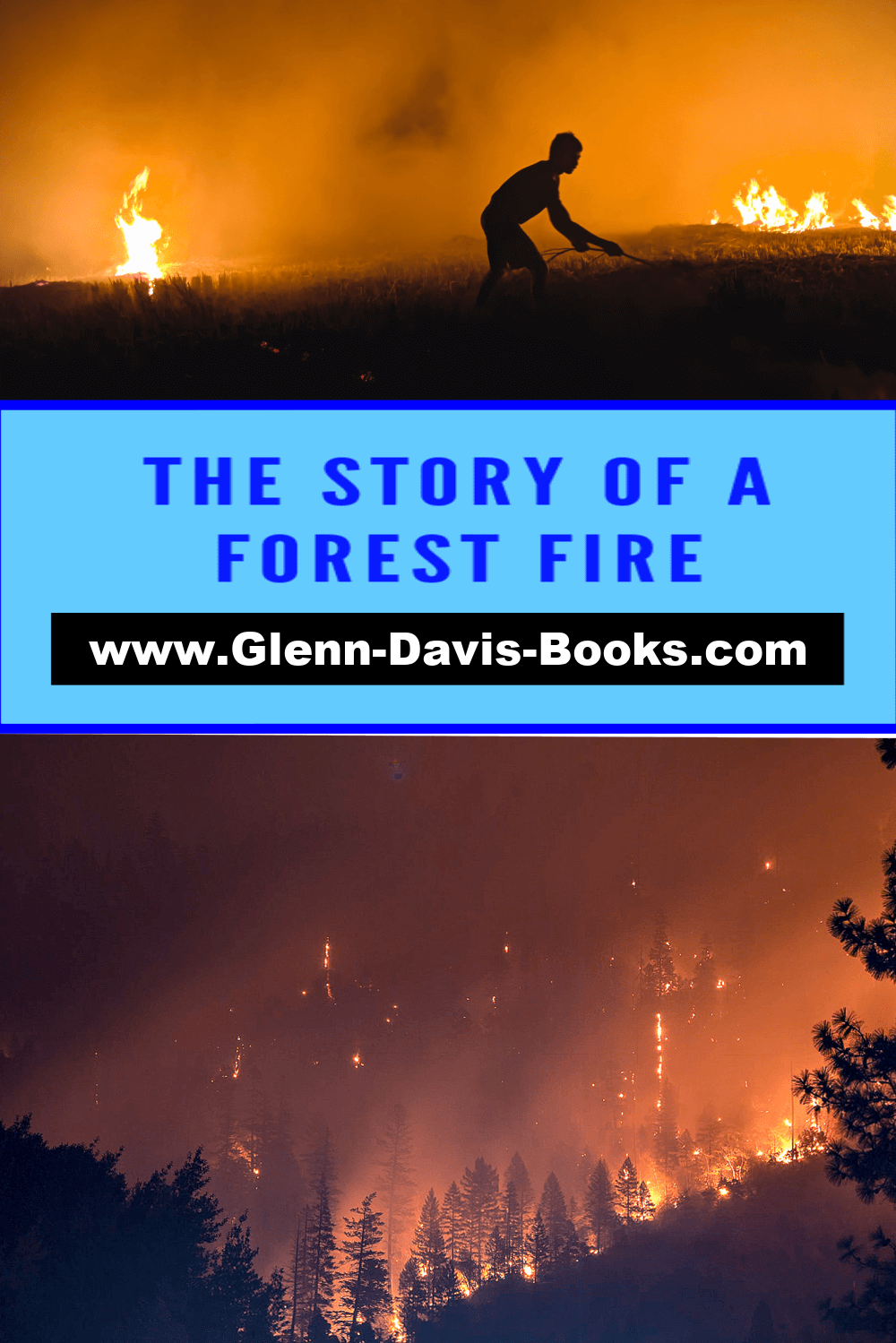

The Story Of A Forest Fire

By Raymond S. Spears

Note: If you purchase anything from links on this site, I may make a commission.

Join our Facebook page.

For more than six weeks no rain had fallen along the southwest side of the Adirondacks. The ground was parched. In every direction from Seabury Settlement fires had been burning through the forest, but as yet the valley of the West Canada had escaped.

But one night a careless man threw a burning match into a brush-heap. When morning came the west wind, blowing up the valley, was ash-laden and warm with the fire that was coming eastward toward the settlement in a line a mile wide.

Soon after daybreak Lem Lawson met the fire on his way to Noblesborough, and warned the settlement of its danger. One man hastened to Noblesborough for the fire-warden, two went up the West Canada to the lumber-camps. The rest of the male population, including boys, hastened down the main road to an old log trail.

It was hoped the fire might be stopped at the open the road afforded.

Will Borson

With hoes and shovels the men dug a trench through the loam to the sand, scattering the dirt over the leaves toward the fire. When the first flames came along, they redoubled their efforts amid the flying sparks and suffocating smoke, but without avail. The sparks and great pieces of flaming birch curls carried the flames over the road into the woods beyond the men, fairly surrounding them with fire.

The men could only go before it, pausing now and then to throw dirt on a spark. Those who lived in the settlement glanced from side to side, wondering if the fire would cross the brook, where they now determined to make another and the last possible stand.

The settlement was built along the brink of a steep side-hill. The bed of the stream was only a few feet wide,--chiefly sand-bar and dry boulders at this time,--and beyond it, toward the fire, was a flat, or bottom, sixty rods wide, averaging not two feet above the bed of the brook.

Should the fire cross the brook, it would climb the hill and burn the buildings. Then it would sweep across the narrow fields of grass, or go round the ends of the settlement clearing, into the "big woods."

One of the fire-fighters was Will Borson, son of the man who had thrown the match, and as he fought with his hoe along the road he heard the men on each side of him cursing his father by name for his carelessness. More than once these men turned on Will, and told him he ought to put that fire out, since his father was to blame for it.

A Daring Idea

Will did his best. Sparks burned holes in his shirt; a flare of sheet fire from a brush-heap singed his eyelashes and the hair over his forehead. When old Ike Frazier cried out, "It's no use here any more, boys!" Will was the last one to duck his head and run for the road up the creek to the settlement.

Half a dozen men were detailed to go to the houses and help the women carry the furniture and other household goods out in the fields to the watering-troughs; the rest hastened to the brook and scattered along it, and threw water on the brush at the edge, hoping the flames would be deadened when they came.

Among them worked Will Borson, thinking with all his might and looking up and down the creek as if the dry gray boulders, with the scant thread of water oozing down among them, would give him some inspiration. The width of the stream was only a few feet on an average, and twenty feet at the widest pools, over which the flame and sparks would quickly jump.

The fire reached the flat at the foot of the ridge and came toward the brook in jumps. The men worked faster than ever with their ten-quart pails. Old Ike Frazier glanced up the stream, and saw Will leaning on his hoe-handle, doing nothing.

"Hi there!" yelled the man. "Get to work!"

"You tell the men they want to be looking out!" Will called back. "Something'll happen pretty quick!" With that he dropped his hoe and went climbing up the side-hill toward his home at the top. Mrs. Borson was just piling the last of her bedding on the wagon when she saw Will coming toward her. He unhitched the horse from the wagon, and had the harness scattered on the ground before his mother could control herself enough to cry:

"Those things'll be burned here! What are you taking the horse for--we--we--"

Then she sank to the ground and cried, while Will's younger brothers and sisters joined in.

Will did not stop to say anything, but leaped to the back of the horse, and away he went up the road, to the amazement of those who were taking their goods from the houses. But he was soon in the woods above the settlement and out of sight of every one.

He was headed for the dam. He had thought to open the little sluice at the bottom of it, which would add to the volume of the water in the stream--raise it a foot, perhaps.

He reached the dam, and prying at the gate, opened the way. A stream of water two feet square shot from the bottom of the dam and went sloshing down among the rocks.

"That water'll help a lot," he thought. Then he heard the roar of the fire down the brook, and saw a huge dull, brick-colored flash as a big hemlock went up in flame. The amount of water gushing from the gate of the dam seemed suddenly small and useless. It would not fill the brook-bed. In a little shanty a hundred yards away were the quarrying tools used in getting out the stone for the Cardin house. To this Will ran with all his speed.

With an old ax that was behind the shanty he broke down the door. Inside he picked up a full twelve-pound box of dynamite, and bored a hole the size of his finger into one side. Then with a fuse and cap in one hand and the box under his arm, he hurried back to the dam.

He climbed down the ladder to the bottom of the dam, and fixing the fuse to the cap, ran it into the hole he had bored till it was well among the sawdust and sticks of dynamite. He cut the fuse to two minutes' length, and carried the box back among the big key logs that held the dam. He was soon ready. He jammed the box under water among beams where it would stick. A match started the fuse going, and then Will climbed the ladder and ran for safety.

In a few moments the explosion came. Will heard the beams in the gorge tumbling as the dam gave way, and the water behind was freed. Away it went, washing and pounding down the narrow ravine, toward the low bottom.

The fire-fighters heard the explosion and paused, wondering, to listen. The next instant the roar of the water came to their ears, and the tremble caused by logs and boulders rolling with the flood was felt. Then every man understood what was done, for they had been log-drivers all their lives, and knew the signs of a loosed sluicegate or of a broken jam.

They climbed the steep bank toward the buildings, to be above the flood-line, yelling warnings that were half-cheers.

In a few moments the water was below the mouth of the gorge, and then it rushed over the low west bank of the brook and spread out on the wide flat where the fire was raging. For a minute clouds of steam and loud hissing marked the progress of the wave, and then the brush-heaps from edge to edge of the valley bottom were covered and the fire was drowned.

The fires left in the trees above the high-water mark and the flames back on the ridge still thrust and flared, but were unable to cross the wide, wet flood-belt. The settlement and the "big woods" beyond were saved.

Sol Cardin reached the settlement on the following day, and heard the story of the fire. In response to an offer from Will, he replied:

"No, my boy, you needn't pay for the dam by working or anything else. I'm in debt to you for saving my timber above the settlement, instead." Then he added, in a quiet way characteristic of him, "It seems a pity if wit like yours doesn't get its full growth."